| National Science Center KIPT | EN RU |

Dates of Life and Activity

Scientific Biography

Awards and Prizes

Scientific Activity

Scientific Achievements

Main Publications

Recollections

About A.I. Akhiezer

Photoalbum

Video

Reminiscences about Yakov Il'ich Frenkel: (A tribute on the centenary of his birth)

A. I. Akhiezer

Yakov Il'ich Frenkel

I had heard about Yakov Il'ich long before I actually met him. Our indirect acquaintance began in 1929, when I joined the Electrical Engineering Faculty at Kiev's Polytechnical Institute. I was profoundly interested in mathematical and theoretical physics. I. F. Ioffe and Ya. I. Frenkel' visited Kiev at that time to present their reports and to deliver lectures. The younger generation of scientists literally idolized them and considered them to be the most remarkable physicists in our country. It was not easy to find room in the jampacked hall where they spoke, but we managed to see and hear Yakov Il'ich.

For my practical work, I was sent to the plant "Svetlana" and the Kozitskii plant in Leningrad. I frequently visited the V. I. Ul'yanov Institute of Electrical Engineering, Leningrad. Together with my new acquaintances, I had the fortune to be present at the debate between V. F. Mitkevich and Ya. I. Frenkel' on the nature of the electric current and magnetic field lines. The debate was very hot and interesting. Mitkevich asserted that magnetic field lines are material on their own. Yakov Il'ich, on the other hand, laid stress on their formal and illustrative nature, assuming, of course, the physical reality of the magnetic field itself. Frenkel' compared the field lines with the meridians which can be passed in any number on the globe. Mitkevich retorted: I do not know Frenkel's meridian, but my meridian is red." This political proclamation evoked a loud applause in the hall. However, we young men were highly impressed by the speech and arguments presented by Yakov Il'ich.

In Kiev, my elder brother Naum Il'ich Akhiezer, who was already a renowned mathematician [1] at that time, looked after my education in the fields of physics and mathematics. So he gave me various books which were necessary for me in his opinion. Among these books were Abraham's "Theory of Electricity" and Frenkel's "Introduction to Wave Mechanics", both of them in German. From Yakov Il'ich's book, I learned about the existence of matter waves which were even described by complex values. I could not make heads or tails of anything from this book, and would have branded it as mysticism and scholastics were it not for the fact that the book was written by Frenkel' himself.

It was not possible for me to study wave mechanics in detail at that time. Hence I had to postpone the problem concerning the origin of matter waves until better times. I busied myself with more specific and "down-to-earth" problems like the equations of mathematical physics, mechanics, and the theory of functions of complex variables. After graduating from the Polytechnical Institute, Kiev in 1934, I was sent to work at the Ukrainian Physicotechnical Institute (UPTI) in Kharkov. It is beyond my comprehension even today how I ended up working with Lev Davidovich Landau, Head of the theoretical division of UPTI, who accepted me in his department after the preliminary examination.

This was the beginning of a hard and complicated period in my life: I had to pass Landau's theoretical minimum, participate in the work of the scientific seminar, and read papers published in Soviet and foreign journals.

I had to dig into a large number of books, both Soviet and foreign, in a quest for the answers to the questions from the theoretical minimum. Once again, I came across Frenkel's books. I especially liked his "Course on Vector and Tensor Calculus with Applications to Mechanics" and "Electrodynamics". These books helped me a lot. It was difficult to grasp quantum mechanics which had to be learned only from the original papers. I recall a curious incident relating to my electrodynamics studies. Much later, after passing all the examinations, I once asked Yakov Il'ich why he had interchanged the magnetic induction and magnetic field strength in his formulas in electrodynamics. He jocularly remarked, "Well, I am a famous muddler!"

We had a lot of work to do in Landau's department at UPTI and it left us with precious little time that we could devote to problems not directly concerning our subjects. Hence, although I did look at the works of Yakov Il'ich, I really got acquainted with them much later.

Before the Second World War, I met Yakov Il'ich several times at various scientific conferences. The more I saw and heard him, the more I liked him for his simplicity, amicability, humor, and his personality.

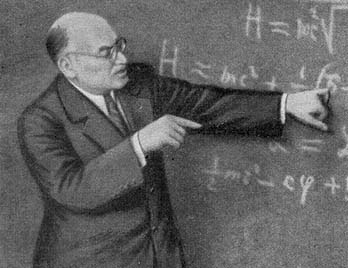

Yakov Il'ich Frenkel at lecture

In 1940, I defended my D. Sc. thesis devoted to the absorption of sound in insulators and metals. Yakov Il'ich was my official opponent. I was literally fascinated with our discussions about the results of my work. As a matter of fact, I realized at that time that he would have solved this problem in an altogether different manner (S. N. Tkachenko, one of his associates, was already working on such problems). But Yakov Il'ich was a remarkable person! He at once accepted my approach in which phonons appeared as real "live" particles.

It should be remarked here that a famous scientist from Moscow, whom I told about my work, compassionately remarked, "Well, after all, what are phonons? Just a matter of expression. You may or may not speak of phonons, and yet arrive at the same results." Of course, this scientist could never obtain the results without phonons. The fact remains that phonon behaves like a real particle obeying a definite statistics. Phonons as "live" particles had been accepted in physics for a long time. They were introduced by both Einstein and Debye in their classical works on the specific heat of solids in which the phonon statistics was naturally taken into consideration. What was new in my approach was that I took into account the kinetics of these particles (quasiparticles, to be more precise) because they are characterized in crystals by a quasimomentum rather than momentum. By considering their kinetics, I obtained kinetic equations for phonons and studied their nonequilibrium distribution caused by an external acoustic wave.

My approach did not raise any doubts in the mind of Yakov Il'ich who strongly supported it.

Later, I understood that Yakov Il'ich could not but support my technique. After all, it was close to his heart, since it was Yakov Il'ich who conceived excitons which are also quasiparticles propagating in crystalline media.

For me, the idea of excitons was the first example of the enormous significance of many ideas put forth by Yakov Il'ich. However, we shall return to this subject. For the present, I shall continue with the story about my D. Sc. dissertation.

While preparing the material for these reminiscences, I recently re-read Yakov Il'ich's evaluation report and was once again impressed at his profound understanding of the solid state physics and, in particular, the problems of transport and absorption of vibrations, as well as the connection between them.

Yakov Il'ich's report contains a paragraph which characterizes his style and outlook as a theoretical physicist. Hence I shall reproduce it here.

"It should be remarked to the credit of the author (of the dissertation—tr.) that he does not tackle the illusory problem of exact numerical calculation of the quantities that interest him (sound attenuation coefficient, thermal conductivity, electrical conductivity, etc.), but is content with establishing their temperature dependence, especially for the limiting cases of low and high temperatures, and with the order-of-magnitude estimates of these quantities, which can be done without completely solving quite complicated kinetic equations."

This evaluation reflects the general approach of Yakov Il'ich towards theoretical works. He was always interested mainly in the idea underlying the physical essence of the problem and not in the details of mathematical calculations (except, of course, in fundamental problems like the hydrogen atom problem). It should be observed here that Yakov Il'ich was well-versed in the mathematical apparatus.

During our meetings and discussions connected with my D.Sc. thesis, I realized that Yakov Il'ich was not only an outstanding physicist, but also a person with remarkable moral qualities. I would like to illustrate this through an example. I once called Yakov Il'ich in Leningrad to settle the date of his arrival in Kharkov. He answered my question and added, "Shura, maybe you need some butter. You have a small child, and it is not difficult for me to bring some butter along." I not only did not request Yakov Il'ich about it, but could not even imagine that Frenkel' would bring me edibles from Leningrad!

When Yakov Il'ich arrived in Kharkov, we went straight from the railway station to my flat for breakfast. However, it was impossible to sit by the table because my young son, who was a brawler, crawled under the table. The situation became unpleasant, but Yakov Il'ich did not spend much time in deliberation, took off his coat, and also crawled under the table. They whispered something to each other, after which the mollified kid crawled out from under the table, holding Yakov Il'ich by the hand. Yakov Il'ich said, "Your Ilyusha is a fine kid, but you must know how to deal with him!" He informed us that his wife patronized a kindergarten and had to deal with small children quite a lot. He also told us that he was on friendly terms with S. Ya. Marshak, the famous children's writer.

In those distant years, not everybody was conversant with Einstein's theory of relativity. When Yakov Il'ich was in Kharkov, my friends and I requested him to drop in at the university and explain in the vice-chancellor's office that the existence of maximum velocity of propagation of interactions does not contradict any philosophical principles and is not the same thing as "extremism" in transport. Yakov Il'ich could expound quite well and was obviously a good explicator. Moreover, he explained that the theoretical physicists working in the university were qualified and intelligent comrades who must be protected. He also supported my nomination to the post of the head of the department of theoretical physics. I headed this department in the university for 40 years.

Yakov Il'ich was always a welcome and cherished guest in Kharkov. Among his admirers were Kirill Dmitrievich Sinel'nikov and Anton Karlovich Walter, whom Yakov Il'ich knew since 1920's when they worked together in Leningrad. Yakov Il'ich always carried his violin during his visits to Kharkov, and they played together with Kirill Dmitrievich who was a very good pianist. This was a real treat for all of us, although it was not the music that was important, but the interesting talks and narratives of Yakov Il'ich about various scientific and everyday matters.

I somehow recall a minor episode which, however, is very characteristic of Yakov Il'ich. We were putting up together in Moscow in hotel "Moskva", and I was sitting and talking with him in his room, when he suddenly got up and exclaimed: I am leaving tonight. I shall go to the refreshment room and buy a cake for the woman on duty on our floor. It must be quite boring for her to sit alone just like that!"

Yakov Il'ich had an enormous physical intuition which enabled him to "grasp" the essence of a phenomenon quickly without a rigorous mathematical description. Using the familiar division of mathematicians into classics and romantics, it can be stated that Yakov Il'ich was a romantic by thought, and a romantic (not a classic) physicist at that, since mathematics for him was not a source of revelations in physics, which is a characteristic malady of the classics.

In this connection, I recall an incident. I was preparing a course of lectures on the "Structure of Matter" which I intended to deliver at the university. Yakov Il'ich happened to be in Kharkov at that time, and I decided to consult him, since I could not cope with the course as far as its logic and inherent structure are concerned. Yakov Il'ich remarked, "Don't strive to put away things in their respective drawers." This meant that there was no need for excessive logical elegance while delivering a general course on physics.

Many years later, we can now look anew at the scientific heritage of Yakov Il'ich. It can be seen that a large number of brilliant ideas were put forth and developed by Yakov Il'ich, and went on to become a part of the golden treasure of science.

Although some of his ideas were attractive at a first glance, they seemed to be short-lived. However, time puts everything at its right perspective, and these ideas of Yakov Il'ich acquired a new life and occupied their appropriate place in the newly developing physics as its indispensable part.

As an example, let us consider Frenkel's pairs. It was assumed in the beginning that even if this idea is genuine, it can be realized for a narrow range of very loose structures in which the heat of evaporation of an atom from a lattice site to interstitial position is not large. However, the development of the radiation solid state physics showed that a simultaneous emergence of a vacancy-atom pair inculcated ("evaporated", according to Yakov Il'ich's terminology) to an interstitial position is one of the fundamental processes responsible for the formation of radiation defects in loose as well as densely packed structures.

For many years (about two decades), Frenkel's excitons met with a guarded, and even skeptical, response. Even Wolfgang Pauli was one of the skeptics. However, the beginning of the 1950's marked the active development of exciton physics which forms a vital part of the modem solid state physics.

Frenkel's famous "kinetic theory of liquids", which exerted an enormous influence on the development of physics and physical chemistry all over the world, was received with skepticism by some "genteel" theorists who were vexed over a large number of author's intuitions and especially the absence of a "small parameter" without which the construction of a theory was incomprehensible. Time, however, is the best judge and Yakov Il'ich's book now ranks among the outstanding works on molecular physics. It is universally known now that this book contained for the first time the fundamental idea that a liquid is different from a gas in its structure and close to a solid because of the existence of a short-range order in the arrangement of atoms.

Of no less importance are the ideas of Yakov Il'ich in the field of nuclear physics. He was the first to realize the necessity of applying the methods of statistical physics for studying the atomic nucleus. He also put forth the important idea that emission of a neutron by an excited nucleus is analogous to evaporation of molecules from a heated drop.

At the end of 1938. the phenomenon of nuclear fission was discovered in uranium. The very next year, Yakov Il'ich presented the theory of fission of heavy nuclei. He set out from the idea that fission should be treated as a consequence of the vibrations of a charged drop. A little later, Bohr and Wheeler used the same idea as the basis of their theory of nuclear fission. The quantitative theory was developed by Yakov Il'ich for small vibrations of a drop while fission is associated with large vibrations. Nevertheless, Yakov Il'ich was able to explain correctly the mechanism and main features of fission. It should be added that small vibrations of a drop are significant in themselves since they form the basis of the modern theory of collective excitations of atomic nuclei.

There are several examples illustrating the brilliant intuition and insight of Yakov Il'ich. Suffice it to say that Yakov Il'ich explained the origin of ferromagnetism independently of W. Heisenberg, and understood the role of exchange interaction in it. Together with Ya. G. Dorfman, he also proposed the theory of domain structure of ferromagnets. He applied the quantum-mechanical tunneling concepts to explain rectification at a "metal-semiconductor" junction. Although some of his ideas did not evoke due response, they survived and form a part of the golden treasure of modern physics.

A perusal of his "Principles of the Theory of Atomic Nuclei" or "Introduction to the Theory of Metals" is really gratifying because of the richness and profundity of his ideas, the clarity of "good" physics in which these books abound, and the mastery of presentation.

Yakov Il'ich remains in our memory as a brilliant scientist and a physicist to the core, a remarkable teacher with rare human qualities. He was humane in the true sense of this word.

Translated by R. S. Wadhwa

[1] N.I.Akhiezer (1901-1989), Corresponding Member of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, was a leading specialist in the theory of functions (Editor's note).

© 1994 American Institute of Physics

This article appeared in Low Temp. Phys. 20 (2), February 1994 [Fiz. Nizk. Temp. 20, 194-197 (February 1994)]

| © NSC Kharkov Institute of Physics and Technology | Designed by Alex Davydov |